Featured Article:

Still There: 50's Employees Built Your LSLP

All LSLP's were made in this, the original Gibson factory.

I've always thought of LSLP's as a continuation more than a reissue, as if they were the 1962 and 1963 Les Pauls that should have been. That fact that your LSLP was built by a good number of the people who built the 50's originals, in the same place with many of the same tools, goes a long way towards proving that point.

I have two stories for you in this article: Originally posted on the Les Paul Forum, one is "Big Al's" tale of visiting Gibson in the 1970's. Apparently, the finishing crew was largely a carry-over from the 50's. The other is from an ancient article from Gibson's website circa 2004. It's about a Mr. Hutchins and his tenure at Gibson. He started a little after the 50s, but he helped build the body of your LSLP and went on to help found the Historic Series.

Thanks for tuning in, sit back and have a read.

FROM THE LPF: "Big Al's" Tale.... In His Own Words:

In the 70's I was an authorised Gibson Repair Tech. In order to claim reimbursement from Gibson for warranty repairs. You would go to Kalamazoo and spend a working week learning all the manufacturing processes and repairing instruments upstairs with the "oldtimers", a group of amazing craftsmen who did all in house repairs.

I was there along with my pals, Seymour Duncan and JIM Lombard, as we were representing the Santa Barbara area.

I was particularly drawn to any of the people who worked at Gibson in the McCarty Era. In fact, Gibson had a big list of all the current employees ranked by seniority on the wall, in a glass frame by the offices. Many of them were still working there from what I saw.

Now this is what happened as best I can recall. I only have my word, and I'm sure Seymour would remember too, as we were both keen on getting deeper insight into the nuts and bolts of the iconic guitars we both loved.

I learned lots of things. I 'll just keep it on topic. Dark, Tobacco Sunburst Les Pauls. I was verry interested in the Tobacco Burst as the 59 I owned was one, and no one ever had a good reason why there were so few.

In those days there was not a big range of colors. Each model had a standard color, with notable Ebony Black finishes, as a rare alternative. SG's, Firebirds and some others got colorful, but in the 50's it was usually one standard color.

Les Paul models from mid 58-60 were supposed to be "Gleeming Cherry Sunburst". So we took the tour, got the corporate presentation and afterwards we hung back to hang with the sprayers. You don't interrogate these guys. You show a sincere interest, some aptitude and affability and knowledge is freely given, you just soak it in.

At some point one of us mentioned the Tobacco Burst and things got lively. The men had become more open and relaxed with us by then, and they got excited by the topic. I can't remember their names, I'll call them Larry and Curley. Larry told Curley to go fetch Moe.

Moe came into the spray booth was introduced to us and we shook hands and got to know eachother a bit. I think they already knew Seymour. Anyway Larry and Curley brought up the reason Moe was summoned as he apparently was the guy who sprayed Les Pauls in the familure shades found on Gibsons Archtop guitars. Moe was a crusty old timer, who we were told sprayed most of the f hole jazz boxes that signature rich brown shaded burst. The other two were ribbing him pretty hard and it seems a few times Moe was pressed into Les Paul finishing and he shot them in brown. If they had a red burst comming into the booth, they were brown when they left.

Moe just hated Cherryburst. He thought it cheapend the Gibson tradition and swore he would never shoot in a guitar in that color. The other two were nodding their heads in agreement and they were all laughing about it. Larry said Moe had his ass chewed for it. They claimed it was a rare thing that only happened a few times before it was stopped and Moe was spared any further duty spraying Les Pauls.

We laughed alot and Moe went back to his custom area to work on the "box" guitars he loved so much. All three of them were MASTERS, wizards at their craft. They even had Moe reshoot a Cherryburst, Tobacco, as well as shooting a regular Tobacco Burst, (not their term, it was simply known as Sunburst to them), after Moe left we heard some more stories, and it was obvious the high esteem they had for his artistry with a spraygun.

I believed them. They had no reason to lie and it rang very true.

Now I wasn't aware of those few really dark scarlet red Darkbursts, but IMO, and it is only a guess on my part, but I believe they were done to hide some minor mineral or flecks. I don't think they were instructed or directed to. I think it was decided by the man on the gun and what he thought looked right. I dunno, but that's my thought. The Tobacco BROWN Bursts, like the 175's, L5's ect. were shot by Moe.

Big Al made another post on this topic on 9-16-2014. Again speaking about "Moe", Al said...

That guy was gifted. He showed me some custom gun stocks he made. The hand cut checkering was a work of art.

The biggest thing I took away from my time in Kalamazoo was how much individuals impacted on the various quriks we ponder and puzzle over now.

In this case individuals had highly visible ones. There were only a few guys who sprayed paint. More was the "Brown" guy, for sure. Look at any true tobacky and compare it to a same era 175 or 335. You can see the simularity.

Though I have no direct knowledge of the deeper red type, I feel it must have been from a guy who laid it on thicker, (different finger control on the spray gun can dramatically change how the color appears), to variations in the premixed barrels of Translucent Cherry Red laqure.

My preference is for deeper vibrant color with a wide feathered gradation. If I was shooting them that's what I would spray.

It is the same for neck profiles. Only a few people did the final neck sanding for shape. I was told by Marv Lamb that he could recognise particular profiles and know who shaped it.

That is the magic where machine, tool, wood and factory workers meld into various, distinct and personal ways that provide such wonderfuly unique instruments within general model specs and identity.

The following is a fantastic article that I found buried in an internet archive. It's original URL was: http://www.gibsoncustom.com/News&Events/news27.shtm It was originally posted back in 2003 and describes the career of JIm Hutchins. Mr. Hutchins built guitars at Gibson for FORTY YEARS. Yes, he probably helped build your LSLP.

The subsequent text is directly quoted from the original article and is the property of Gibson Guitar. I figured they wouldn't mind if I posted it since it has been "offline" for a decade by now. :) I divided it into paragraphs to make it easier to read.

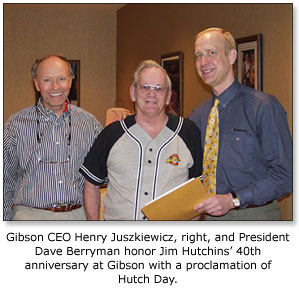

Forty years to the day after Jim Hutchins began working at the Gibson guitar plant in Kalamazoo, Mich., Gibson CEO Henry Juszkiewicz has proclaimed March 25, 2003, Hutch Day. To thousands of guitar aficionados who are familiar with the signature of “James Hutchins” on the label of a Gibson archtop, Hutch represents a critical link to Gibson's long history of handmade instruments.

“We just wanted to say how much we enjoy working with you and how much we feel you're a part of our family,” said Juszkiewicz, as he and Gibson president Dave Berryman presented Hutch with an official letter proclaiming Hutch Day. “We wanted to recognize this special day and everything you've done for us.”

An avid hunter, Hutch will receive a new 10-gauge shotgun from Gibson, along with a special plaque naming a part of Gibson's Custom Shop after him. Hutch began his career with Gibson in Kalamazoo, Mich., where Gibson was founded and based until headquarters were moved to Nashville in 1984. “I was working for Checker Cab for about three weeks,” he recalled, “and I saw the smokestack that said 'Gibson.' I went home and told my wife, 'I wonder what they do there?'” “I went in the front office and asked if they were taking applications. They said yes, and they asked me 'How soon can you have it back to us?' I said, 'About an hour.'” Hutch interviewed with Julius Bellson, who had been working for Gibson since 1935 and would go on to write the first history of the company. “He said there was an opening in the mill room running a band saw,” Hutch said, “but when I got there the next morning I found out the janitor took that job. So I started as a janitor. It took about four years, and I ended up in the pattern shop, which was the top job there.”

Hutch received a piece of good advice from his father that served him well at Gibson. “My dad told me, keep your mouth shut, listen to the older guys, and you'll learn. It was the best advice I ever got.” “Some of the guys had been there 30, 40 years. You did it the old way because that's the way the did it. Then later on the boss that I had said to find a better way. And that's the part I really liked. Make the project easier but keep the quality there.” The pattern shop was the design shop in those days. “The pattern shop makes the whole guitar,” Hutch explained. “You present the guitar when you're done with it, then you make the tooling. Keep in mind that we didn't have NC (numerically controlled routers), just shapers and saws.”

In the mid-to-late 1960s, Hutch and his colleagues in the pattern shop worked with some of the best guitarists of the period, designing guitars for Tal Farlow, Barney Kessel, Herb Ellis and Howard Roberts. The highlight of his Kalamazoo years came near the end, when Chet Atkins left Gretsch and became a Gibson artist. “Engineering worked differently then,” Hutch recalled. “You'd take a model and have an engineering meeting to discuss the project. We had as many as nine pattern makers and one of us would get the project. Fortunately, I got Chet's project. The Country Gentleman was pretty much my baby. We built 300-and-something up there as it was going down.”

Gibson was a sinking ship in 1984 when the company closed up the Kalamazoo plant and moved to Nashville (to a facility that had been built in 1974). Hutch hadn't planned on making the move. “I used to remodel bathrooms and kitchens,” he said, “and I set that business back up. I had built a big shop for that. But they just kept making offers - would you come down for a year. They nagged me and nagged me. Then they got smart and flew my wife down here. She's the one who really wanted to stay.” Hutch was a key figure when Gibson established the Custom Shop as its own division, based around the Historic Collection, in 1993. “Rick Gembar (general manager of the Custom division), when he took Custom, said 'What do you need?'” Hutch said. “I said, The best wood we can buy and the best people we can get.' Rick has backed me 100 percent. We doubled production several years in a row.” Although his title has changed numerous times through the years, his business card still carries the title he had 10 years ago: Senior Design Engineer, Historic Collection. He's not planning on retiring when he turns 65 in December, although he and one of his sons have bought 120 acres of land in nearby Waverly, Tenn., where he's thinking of building a home and devoting more time to his other passions - guns and dogs.